Simulating Voter Errors with ACT-R

by Josh Engels

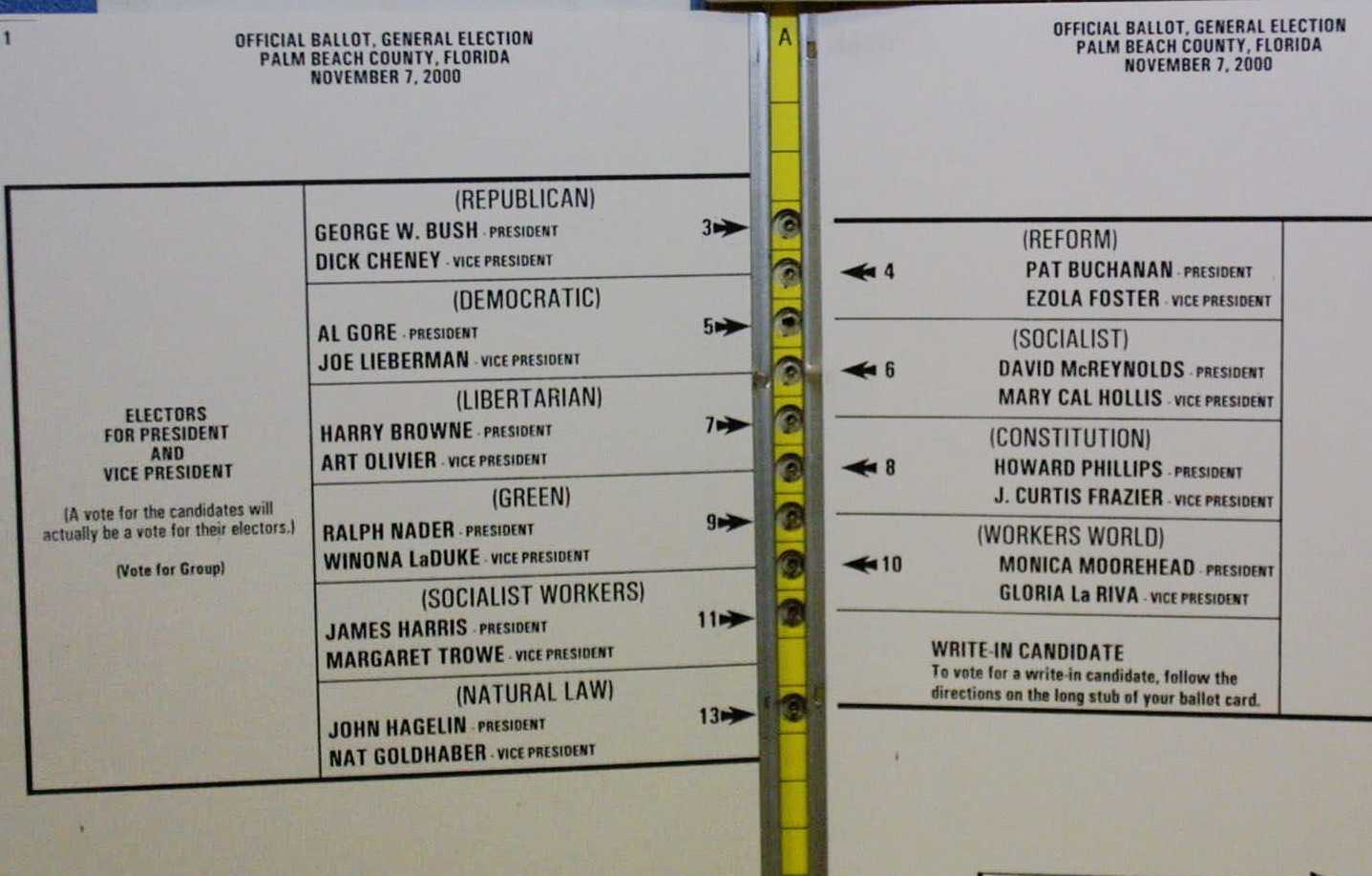

Badly designed ballots may not seem like a pressing problem, but they have already swung multiple elections. For instance, consider the following ballot:

At first, the ballot looks fine, doesn’t it? If you want to vote for Al Gore, he’s the second candidate down the list, so just fill in the second bubble. Easy, right? If you thought that, you’d be wrong! The actual bubble for Al Gore is the third one down. Don’t worry, you wouldn’t be the only one to make that mistake. In fact, the authors of [1] show that in 2000, this “Butterfly Ballot” mislead so many voters, it cost Al Gore the presidential election.

This isn’t the only time bad ballot design has swung a presidential election. More recently, an article by the Washington Post noted that the Broward County ballot significantly impacted the results of the 2018 senate race in Florida [2]. In both of these cases, an independent ballot review conducted before election day may have been able to flag the problems before voting began. Unfortunately, such reviews are time consuming and expensive. It simply isn’t feasible to run reviews for tens of thousands of different ballots every two years.

Enter ACT-R and Rice’s Human Computer Interaction (HCI) Lab’s voting project. ACT-R is a cognitive architecture—a system for writing programs that accurately simulate human behavior. All human biases and quirks are included as features, not bugs. The Rice HCI voting project seeks to use ACT-R to create a tool that can predict if a ballot will cause errors. The tool will accept a ballot, run thousands of simulated ACT-R voters on it, and then report any systematic errors the simulated voters make.

While I was at Rice, I spent a year working in the HCI lab on this project. My main contribution was a prototype of a complete modular simulated voting system in ACT-R. Like many human activities, voting is actually composed of smaller pieces when examined closely. In our system, we broke voting down into:

- Macronavigation: visual navigation between races

- Visual Encoding: separating the components of a race into the title, candidates, and parties

- Mirconavigation: visual navigation within a race

- Selection: clicking on the chosen candidate’s bubble

The modularity of the system meant we could write different “strategies” for each of these components and mix and match them to create simulated voters representative of the general population (not everyone votes the same way, and a certain way of voting may cause errors on a given ballot). Excitingly, the HCI lab was also running eye tracking experiments on human voters at the same time, so we had a constant stream of data on how people vote in the real world. Using the modularity of the framework, we were able to immediately implement these strategies and run them on simulated ballots.

The most interesting strategy we implemented was the “snake strategy,” which was a unique macronaviation strategy that instead of going top to bottom and then left to right, went left to right and then top to bottom (yes, real people vote like this sometimes).

The gif shows a sample run of the snake strategy. The red circle represents the “attention” of the ACT-R simulated voter. Notice that the simulated voter misses the Railroad Commissioner race!

In our paper [3], we analyzed snake voters on over 6000 random ballots and reported the resulting error rates. We found that the strategy was most likely to skip visually small races, races in the bottom right corner of the ballot, and races visually far from races in the prior column.

There’s still a lot of work to do before a tool like this is usable. We need to completely map the space of human voting behavior so we can ensure the tool fairly represents the entire voting strategy space. We need to write parsing routines that can take ballots and turn them into a form ACT-R can understand. We need to wrap all of this up into an easy to use tool and convince people to use it. These problems are daunting (and this list isn’t nearly exhaustive), and the system I worked on may or may not eventually make it to a county near you.

However, these problems are the sort of problems that may stick around for a while. Unlike “natural” machine learning problems like image classification or product recommendation, it isn’t immediately clear to me how we can use recent AI advances to better find badly designed ballots. The set of labeled examples is small and the set of possible ballot designs (the input space) is huge. Moreover, heuristic based approaches also suffer from the huge input space, and moreover will especially struggle on any new ballot design flaws that haven’t been seen before and “hardcoded in” to the system. Systems that are designed to mimic human behavior like ACT-R don’t need any training data and can simulate emergent and organic error behavior. Thus, I think that they will likely outperform convolutional neural networks or hardcoded heuristics for the forseeable future. In the spirit of Winston Churchill, ACT-R simulation is the worst ballot error identifier, except for all of the other ones (please don’t hesitate to let me know if you have a better idea, I’m interested!).

Citations:

[1] - The Butterfly Did It: The Aberrant Vote for Buchanan in Palm Beach County, Florida

[2] - How a badly designed ballot might have swayed the election in Florida

[3] - Missed One! How Ballot Layout and Visual Task Strategy Can Interact to Produce Voting Errors